I was surprised and honored to be invited as a keynote speaker last month in Atlanta for an innovative national health care organization. A few years ago, my brother introduced me to his friend, the CEO of this company, via e-mail. He is a remarkable leader and writer who follows my cancer journey with kindness and support. We agreed I would focus part of the talk on the terminal cancer diagnosis and how I stay positive, even joyful, despite this challenge. I knew the team was young, and I wanted at the very least to be interesting, and if possible, inspirational.

I knew it was not going to be easy to simmer my life’s journey and message into one hour. I had also just learned the cancer had advanced beyond my brain and bones, into the liver and lungs. I sincerely was “walking the walk” and not just “talking the talk” as they say in A.A.

At one point, after several weeks, I found myself fretfully pawing through fifty pages of notes, books and several outlines spread over my desk, chair and floor, but I still had no theme.

I have learned when this happens while writing, I need to set it all aside and take a break for a day or even longer. Then I start fresh on a blank page with an open mind. I did that here. I began by creating a list of “Books that Help Me Live a Good and Happy Life,” something I have wanted to do ever since I got the terminal diagnosis to give my three sons. Next, I gathered together all my favorite quotes and poems, which I have been collecting for years. I did not write a single word of the talk that day, but I noticed two recurring themes in my favorite works: overcoming tragedies and unconditional love.

It was then, surrounded by my beloved books, quotes and poems, that I received the answer on how to put the pieces of the talk together. Something a friend told me in passing months earlier, came to mind.

She had mentioned an ancient Japanese method of repairing broken porcelain that uses gold to fill the cracks. I remembered loving that idea immediately— more than Leonard Cohen’s famous lyric, “there is a crack in everything and that is where the light comes in.” For some reason when I pictured being cracked up inside, I tended to feel a harsh wind coming in, not the light.

This method of restoring breakage with gold is called Kintsugi (also known as Kintsukuori) and translates as “golden joinery.” I did some quick research and discovered that Kintsugi is an outgrowth of the Japanese philosophy of Wabi-Sabi, which honors the beauty of imperfections.

The Kintsugi artisan uses gold or other precious metal mixed with epoxy to repair the broken piece. This method emphasizes, rather than hides, the breakage. The repaired piece is often considered even more beautiful than the original.

Kintsugi embraces the breakage as part of the object’s history, instead of something unacceptable to be hidden or thrown away. This is the opposite of what I was taught. I learned that I was supposed to be perfect, and that I must hide any imperfections. This belief is imbedded in our culture: if something is broken, toss it out; if something is flawed, hide it.

Kintsugi was the perfect metaphor for my talk on how I was able to find healing in a life that for a long time, was not only cracked, but broken apart—and, in a few places, shattered beyond recognition.

When I was suffering as a child in a home filled with violence, alcoholism and poverty, my maternal grandmother would take care of me and my younger brother almost every weekend. I remember rushing in to hug her ample body, always in a faded small-print dress, her cheeks red from baking, gardening, making soap and canning. My grandparents created a small farm in their inner city backyard. Whatever else they needed, our grandfather built by hand. They raised four children during the Great Depression through their hard work and faith in Jesus. Every night we said the rosary, and every morning went to Mass. Afterwards, I could swing under the grape arbor for hours, sit at the oak table in her kitchen, eating fresh apple pie and watching her cook. We did not say much, but I basked in the warmth of her loving presence. During those frightening times of my life, my grandmother healed me with her unconditional love.

In my early twenties, with my grandparents and parents dead, I turned to alcohol to block out the pain. I constantly wished that my childhood had been a different one, that I had been born into a different family with different circumstances. I resented spending most of my time trying to recover from the damage. It was hard work trying to fix myself, and to be honest, that never really worked anyway.

Learning about Kintsugi helped me look back and realize that my greatest wish was to be unbroken pottery, instead of who I was. That caused me so much suffering because it was impossible. When I finally had the courage to show those broken edges to others— to my brother, to dear friends, in A.A., in counseling and in safe communities— I received acceptance, and was loved and respected just the way I was, in the same way my grandmother did. My broken parts were transformed into what students of Kintsugi call “precious scars” which honored my whole life, leaving nothing out.

There are many ways to find healing beyond what I share here. It can be a painstaking practice—mine was not quick or easy, and it is still ongoing— like the skill and care required to do Kintsugi restoration. Through it all, I keep coming back to love as the answer, the golden repair that has lasted.

I found that I needed to find unconditional love for myself too, and not just seek that from others. Then I found that I could begin to love others’ whole beings without judgment. I believe this helped me be a far better parent, friend and family member, and it changed the course of my professional life. Best of all, others who are on difficult healing journeys seem to find inspiration when they see my extensive golden scars, and for that I am grateful.

I no longer think of my broken parts as wounds. They are part of my history, and who I have become. As an ancient Kintsugi quote says, “The true life of the bowl began the moment it was dropped.”

My talk was not perfect. They gave me a standing ovation anyway. I had the honor of hearing individually from a number of the participants, who courageously shared their personal stories with me. Together we created an opening of mutual care that is rarely seen in a business setting.

One of my mentors, Dr. Rachel Remen, pioneer of holistic medicine, co-founder of Commonweal Cancer Help Center and best-selling author of Kitchen Table Wisdom tells a story in her book about meeting Dr. Carl Rogers, the humanistic psychologist. When she was a young doctor she saw him demonstrate his method which he called “Unconditional Positive Regard.” A colleague of hers volunteered to be the “patient” and he got up on stage with Rogers. Before he began the demonstration, Dr. Rogers paused a moment, looked at the audience and then said this:

“Before every session I take a moment to remember my humanity. There is no experience that this man has that I cannot share with him, because I too am human. No matter how deep his wound, he does not need to be ashamed in front of me. I too am vulnerable. And because of this, I am enough. Whatever his story, he no longer needs to be alone with it. This is what will allow his healing to begin.”

I can add nothing to these words. They are pure gold.

There are three types of Kintsugi repair. The first level is when all pieces are available and the cracks are filled with gold to restore the piece:

The next level is when small pieces are missing. Those areas are completely filled with gold:

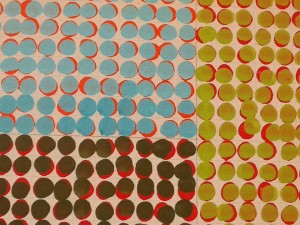

Last, when large areas of the piece are missing or shattered beyond repair, the artisan will take fragments from unrelated pieces to create a patchwork design. This is the one I identify with the most:

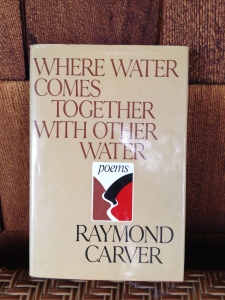

Below are the poems, and quotes I wove into the talk, along with Kintsugi, and my personal—still growing—book list I shared with the group afterwards.

The Guest House by Rumi

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they are a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice.

Meet them at the door laughing and invite them in.

Be grateful for whatever comes.

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

—Copyright 1997 by Coleman Barks. All rights reserved.

From The Illuminated Rumi.

Love your crooked neighbor

With all your crooked heart.

—W.H. Auden

The sun never says to the earth,

“You owe me!”

Look what happens

with a love like that—

It lights the whole sky.

—Hafiz

Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean-

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

—Mary Oliver

Otherwise

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach. It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.

At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

—Jane Kenyon

Quotes:

You may not find a cure, but you can still receive healing.

—Michael Lerner, Co-founder of Commonweal Cancer Help Center, Bolinas, California

It does not really matter what we expect from life, but rather what life expects from us. We are being questioned by life, hourly, daily, moment by moment. Our answer—to respond with right action and right conduct.Life ultimately means, taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems, and to fulfill the tasks which are constantly set for each individual.

—Viktor Frankl

Viktor Frankl taught that everything can be taken from us but one thing—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances. We cannot change these circumstances of being human, (pain, illness, loss and death) but we can change our minds and thoughts.

There is no enemy. We have stopped fighting anything and anybody.

The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous

“Can this be Okay?”

—Mark Nunberg, Guiding Teacher

Common Ground Meditation Center

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Be kind whenever possible.

It’s always possible.

—Dalai Lama

Books that Help Me Live a Good and Happy Life:

Holy Bible, New Testament

Kitchen Table Wisdom, Stories that Heal, Rachel Naomi Remen, M.D.

Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor E. Frankl

The Places that Scare You, A Guide to Fearlessness in Difficult Times, and When Things Fall Apart, Heart Advice for Difficult Times,Pema Chodron

The Girl Who Threw Butterflies, Mick Cochrane

My Experiments with Truth, An Autobiography by Mahatma Ghandi

Letters to a Young Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke

Meditations, Marcus Aurelius

Alcoholics Anonymous, Bill W.

The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran

The HeartMath Solution: The Revolutionary Program for Engaging thePower of the Heart’s Intelligence, Howard Martin and Lew Childres

The Velveteen Rabbit, Marjery Williams

Infinite Vision, How Aravind Clinic Became the World’s Greatest Business Case for Compassion, Pavithra K. Mehta, Suchitra Shenoy

The Gift, Poems by Hafiz

No Mud No Lotus, The Art of Transforming Suffering, by Thich Nhat Hanh

Tattoos on the Heart; The Power of Boundless Compassion by Father Greg Boyle